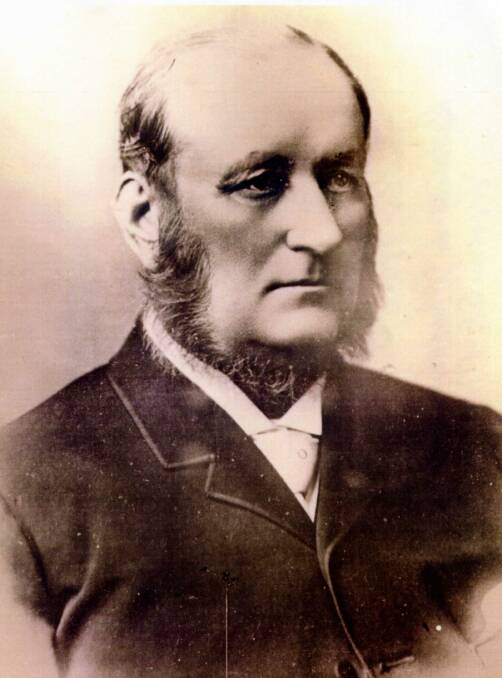

Appointed in 1856 as chief engineer for the colony's fledgling railway, John Whitton is remembered as the 'Father of NSW Railways'.He often visited Mittagong and a plaque commemorating this was unveiled in 1998 at Mittagong's Sturt Gallery by railway historian David Burke and Dr John Simons, Berrima District Historical Society archivist.During his working years, Whitton often spent holidays at a guest house in Mittagong known as 'Marchmont' and continued to do so after his retirement in 1890. Feeling unwell in Sydney's humidity in February 1898, he came up with his wife, hoping the cooler air would revive him. As usual they stayed at Marchmont and he rallied briefly but died a few days later on 20 February, aged 79. His body was taken back to Sydney by train next morning.Marchmont, destroyed in the 1939 bushfires, was on the site where the Sturt Cafe is now located. In an address prior to unveiling the plaque, Dr Simons outlined Whitton's achievements."John Whitton's training on the railways of England accustomed him to tracks that, for the most part, kept to level grounds or climbed gentle grades. I like to think of him, when he arrived in NSW in 1857 and had studied the diverse nature of the country through which he was required to construct an extensive railway system, squaring his Yorkshire shoulders and saying 'Aye, laads, 'ere's a bit of a do, but reckon we'll manage an all'. And so he did by designing and successfully completing spectacular works of engineering, such as his viaducts and tunnels, and the Lithgow Zig-Zag, that are still regarded with wonder and admiration by railway men the world over. He was certainly a remarkable man and a great engineer. The Sydney Morning Herald opined in its 2-column obituary and valediction at his passing, that 'the Colony has a great deal to thank Mr Whitton for in laying the basis of its railways'.But geophysical difficulties were not the only kind he encountered. The Colony's Government had no sooner appointed the man to do the job, telling him he was in sole charge, when politicians began interfering and arguing. Whitton had to fight strenuously against moves to break the gauge of the lines at Bathurst and Goulburn, his opponents arguing that narrow-gauge lines or - preposterous thought - horse tramways, could service the more remote areas. Fortunately he eventually won the battle, only to find he had another to fight, and win, in getting the lines extended to Albury and the Queensland border.His ability to persuade was due to his being 'a man of professional training, great rectitude of character, independence and foresight' - again from the Herald.Naturally, his successes soured the losers who probably felt some spiteful glee when, on the occasion of his retirement, they managed to have the amount he had been promised as his pension cut by half."Dr Simons continued his address by asking: "Why did Whitton choose Mittagong? Sentiment? A very plausible reason since Mittagong station with its refreshment rooms was one of his larger designs - plausible, perhaps, but not convincing.So why Mittagong rather than nearby Bowral, a town that was developing rapidly? He may have thought of it but not, I imagine, for long. The speed of Bowral's growth was due to it becoming fashionable and desirable. The city 'gentry', appreciating the climate and taking advantage of Whitton's conveniently placed railway, saw it as the perfect place for a summer retreat that provided escape from the tiresome, humid summers of Sydney.By 1890, country houses and retreats about Bowral/Burradoo were being erected at a great rate as their owners appeared to pursue a collective ambition to make Bowral the Point Piper of the Southern Highlands. The town and the pervading social pretensions would not have appealed to Whitton, particularly as some of the individuals involved would have been the critics, or outright opponents, of his ideas and aims for railways.Mittagong was a much different town. In the 1880s and 90s it still held an optimistic view of its industrial future. The Iron Works continued to be regarded as promising, the Joadja Shale Oil production was in full swing, and so was production from the Box Vale Coal mine. This general belief in the town's economic future based on technology would be dashed in the first decade of the 20th century.But while that belief held, the spirit of the town would have been just what John Whitton understood and appreciated. That is why I believe he chose Mittagong."This article compiled by PHILIP MORTON is sourced from the archives of Berrima District Historical & Family History Society, Bowral Rd, Mittagong. Phone 4872 2169. Email bdhsarchives@gmail.com. Web: berrimadistricthistoricalsociety.org.au

Subscribe now for unlimited access.

$0/

(min cost $0)

or signup to continue reading